The studio visit for this blog finds me speeding out on the Underground

through the western suburbs of London, passing through sports grounds,

allotments, and then fields. Martin was born and brought up in the area where

he now lives and his purpose-

built studio is at the bottom of the family garden. The immediately obvious feature is the huge

Harry Rochat press. It looks very heavy

to operate, but he explains that it’s 16 to 1 gearing means that the huge wheel

can be turned with a very light touch. He

regards it as ‘the Rolls Royce of presses.’ Martin bought it many years ago, with

money saved up entirely from print sales, over a period of several years. He has only ever made prints – he has never supported

his practice with teaching or other roles.

This must have taken not just ability, but a lot of canny strategic

thinking, so when we sit down with a cup of tea and he relates his roller

coaster journey through eight years of art education, I am rather taken

aback.

Martin spent many hours as a child working alongside his mother in the finishing department of a graphic design and commercial print factory where his father was employed. He earned money by bagging up and labelling the printed material.

He remembers watching the litho plates being made and wound around the rollers, and the printed matter emerging from the machinery. His father was very skilled in all aspects of the work, and eventually became managing director.

Martin recalls that on bank holidays, their garage would fill up with piles of numbered pages set out on decorating tables, and they would spend three days walking around, collating the pages into the finished items and then putting everything into envelopes in the family kitchen. Martin remembers all this quite fondly.

| |||||

| 'TRIPLE A' - an archetypal Martin Langford etching |

Schooling was to prove more problematic. Martin’s sense of humour was irrepressible from the start. He had a short attention span, was rather hyperactive, and loved to keep everyone entertained with jokes and pranks. Studying for A Levels, he concentrated heavily on art and struggled in his other subjects. The fooling around reached the point where, he acknowledges, it was slowing down lessons. One morning, the headmaster called Martin into this office and told him not to come back to school tomorrow, or ever. ‘I spent the next three weeks walking around Ruislip Woods with my camera thinking ‘My life is over’.

A few years later, Martin was to discover that he had a type of dyslexia which predominantly affects short term memory. Although he points out that the tests he took also revealed that he had an excellent memory for numbers.

With his mum’s help, he found the last London college still interviewing for the following autumn term, and so he went to study interior design at the Willesden College of Technology. Fortunately, the course included modules on subjects like life drawing and architecture.

‘I would twist a lot of the project to bring humour into them. My drawing was improving, and I loved making comic strips.’

|

| Sketchbook page |

Following a college trip to Amsterdam, Martin’s response was to make an installation depicting the city’s red light district. He worked incredibly hard on it, but this was an institution run by high-minded design tutors. ‘They wanted to fail me, but there was no way that was going to happen. I went to the staff room and refused to leave until they gave me a pass.’ Having survived once more, Martin studied foundation at Watford College of Art and Design. ‘It was excellent,’ he recalls. He encountered a down-to-earth printmaking tutor who introduced him to etching. ‘I loved its graphic quality. I could see its potential in terms of comic strips, which I still fancied doing as a career at that stage.'

He still came close to being thrown out again though, by attempting a dangerous dare which involved crossing the facade of the building by means of a narrow ledge. Spotted from below by the Dean, he was saved from expulsion by his printmaking tutor, who pleaded his cause.

Next up: a Fine Art degree in Plymouth, specialising in printmaking. Martin did not get on with the frequent theoretical discussions about art. One tutor commented during a critique session. ‘Well, I can see we’re not going to get anything out of this one.’ A final project led to him making a winged papier mâché giraffe which he suspended from the ceiling. It was not appreciated. Still, Martin managed to scrape a pass so he was off again, to a two year postgraduate course in Advanced Printmaking at Central St Martin’s college in London. It was supposed to be part-time, but Martin says ‘I was actually in there most of the time - I just got on with it.’

Renowned printmaker and tutor David Gluck clearly understood what made Martin tick. He introduced him to the mezzotint process. Martin loved this intensive, laborious method of engraving and he practiced it for around eight years. He believes his work in the medium helped him to be elected as a member of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers. Then Martin broke his elbow in a cycling accident, which made the physical labour of mezzotint impossible. So he returned to etching, but he soon found ways to make that just as labour intensive and challenging.

When an idea calls for it, Martin will make a multi-plate etching in colour, but much of this work is done in black and white. This is probably because Martin’s images are almost all either humorous, or convey a powerful, direct message – often both. They are consequently quick to grasp, and I wonder if he ever gets frustrated by working so hard for months on a humorous image only for the meaning to be conveyed in seconds?

‘Yes, he laughs, ‘Every day! But that in itself amuses me!’ We discuss why people still wish to buy satirical

prints, when funny images are abundant and freely available on social media. ‘You

have to get under people’s skin.’ And because

his observation of human nature is so acute, as well as warm and empathetic, he

does this, again and again.

And of course, 'People appreciate the skill and effort that goes into it.‘ He has found, like so many artists, that time and thought put into an artwork results in a deeper, more engaging and durable image.

Martin is never short of ideas. ‘The more you experience you have with life, the easier it is to come up with ideas. ‘Sometimes a thought becomes an idea for a print straight away. Sometimes he looks back over his old sketchbooks. ‘Other things form over long periods of time and develop.’

|

| SKETCHBOOK PAGE |

He doesn’t take a sketchbook around with him though. ‘It’s just notes. It’s really badly drawn, it’s almost nothing and that doesn’t matter. It’s just for me, and the real work begins when I start to work it out as a finished piece of drawing, which can take weeks with the more intricate stuff.’

And then the etching process itself can take weeks or even months. ‘And not all of them work out, so you’ve lost a quarter of a year! But you’ve got to look at it more philosophically than that… When I was younger, I used to get really frustrated when the prints didn’t work. But as I’ve got older, I think hold on a minute; it’s actually okay that it doesn’t work. Printmaking is problem-solving which I love.

It’s supposed to be difficult. You need to worry when it’s easy. If you come up with something and it’s easy, you’re doing something wrong. Every piece that I make I’m thinking, is it going to work? It’s always full of self-doubt as well that comes into it. I start a piece of work and I’ve still got months to go on it and I’m thinking. Are you sure, Martin are you sure?

Everyone needs their internal critic, but you’ve got to control it. You just have to think stop it…..just get on with it! You’ve got to hang on and have the confidence to carry on with it. And then you never know how it’s going to be received. ‘

So from his sketches, Martin does an intricate line drawing, using fine drafting pencils and sometimes a magnifying glass.

|

| Fine drafting pencils |

| ||

| Martin sometimes uses a magnifying glass to draw |

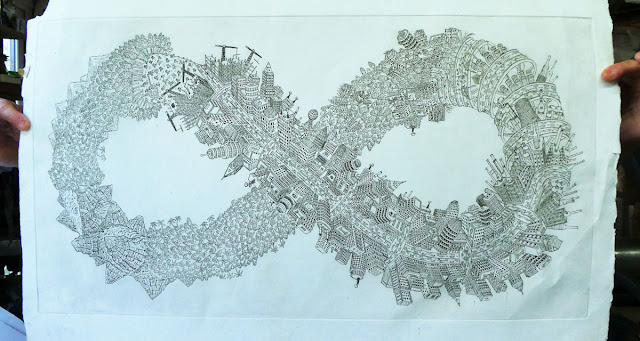

Below is the drawing of his recent etching ‘And so on…’ This extraordinary work won the Stuart Southall Print Prize at the Royal Society of British Artists' Bicentennial Exhibition in March 2023.

|

| 'And so on...' pencil drawing |

|

| 'And so on... ' pencil drawing (detail) |

Martin does not add any areas of tone or shading to the drawing before he starts etching the plate.

‘I don’t want it to be a purely reproductive process.’ He feels that if you simply copy across areas of tone from a black and white photograph, for example, you are not putting enough of yourself into it. From the drawing, Martin makes a line etching and takes a first proof.

'And so on...' line etching first proof